Woody Herman’s Four Brothers: Herbie Steward, Zoot Sims, Stan Getz and Serge Chaloff

You might have heard of “Drop 2”. It’s a technique for harmonising a moving line. This was originally used in arranging for orchestras and big bands, but it’s also used by pianists and guitarists when soloing or comping. Often when they have to follow a horn player who has just spent a solo stomping the number into a pink miasma then tosses over the remaining entrails, hoof jelly and sticky eyelashes, while basking in the applause. The pianist or guitarist nods pleasantly, lets the hubbub die down, then casually demonstrates that they can solo too, but sounding like four horns at once…

Does such one-upmanship really go on? Actually yes, but it’s usually healthy. Anyway, let’s skip over all that for now and just say that using techniques like Drop 2 plays to the instrumental strengths of the piano and guitar and provides a nice change in texture.

The technique is easiest to apply on a scalar line over relatively straightforward harmony, so you’re thinking basically in terms of harmonising the home scale (whatever it may be at the time). Start by working on tunes where the melody moves for a while in clear scale steps, like There Will Never Be Another You. Here are the basics of the approach.

Think of Drop 2 as a lateral process, rather than a vertical event. While any isolated chord might be “in” Drop 2 (a lot of the four-note voicings most natural on the guitar neck are “in” Drop 2), it can be more useful to think in terms of “harmonising a line in” Drop 2.

While you can use the concept for any four-note chord voicing anywhere, the core principle is that you can harmonise every tone of the scale with inversions of either a tonic 6th chord (eg C6 – CEGA) or a dominant 7b9 chord (G7b9 – G B D F Ab).

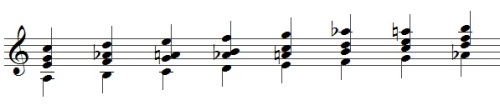

You start with these chords voiced as close as possible. So, eg here is C major harmonised (melody on top):

FOUR-WAY CLOSE

- No root in the dominant chords, I hear you cry? Doesn’t matter, the bass has got that. Much more important that the b9 is adding a diminished flavour to the proceedings.

- Note the symmetry and smooth movement – every voice is playing the same scale and moves in tandem with no repeats or crossing.

- You’ll hear this sound everywhere from classical orchestration to ragtime, Sousa marches and early swing arrangements, even the Andrews sisters – well, okay there were only three of em, but it’s the gist.

- It’s called “Four-Way Close” because that’s what it is – four chord tones voiced as closely as possible together.

Harmonically, you’re hearing C6 and G7b9 alternating with each other – oh and there’s a half-step added between 5th and 6th to keep the tidy alternating pattern. This also leads you to the concept of the jazz major bebop scale – C D E F G G# A B (although jazz certainly didn’t invent it.)

By the way, if you want to do the same in C minor, just alter the base tonic 6th chord from CEGA to CEbGA. Keep the G7b9 chord the same.

So far, so ho-hum. But by spreading the voicing (literally “dropping” the second voice down an octave) you get a broader sound and a richer interaction between tones – a much less obvious, traditional, organ-like “girl tied to railway tracks” sound:

DROP TWO

Pianists take these voicings in two hands – there are different ways of doing it, but the most common approach is to play the dropped note in the LH.

Chord too cramped? Drop the second voice to make more room

It takes a while to learn to “see” these voiced scales the right way. It helps to think of them from the top down – this is a scale with slightly spread voicings hanging underneath it. Another hurdle to understanding is that quite a lot of people aren’t terribly familiar with tonic 6th chords.

Of course, once you’ve got the hang of the basic structure you can spend hours experimenting and messing with internal voice movements to work in other tensions (particularly on the dominant chords). One of the benefits of Drop 2 is that you get more room for manoeuvre within the voicing for alterations.You can also alter this basic model to cover different chord types. Actually, if you think about it, by learning the C6 G7b9 set you’ve already learned a set that goes over Am7 E7b9. (Which can be played over A minor, but don’t forget there’s an Am6 version as well.)

It is actually possible to solo extensively in this style*, with a lot of practice. But just sprinkling in a little of it here and there can work wonders.

Other options (more commonly applied to band arranging than chording instruments) are “Drop 3” and “Drop 2 & 4”. Full big-band arrangements (standard being 5 saxes AATTB, 4 trumpets and 4 bones – one maybe a bass) routinely contain “drop” voicings in combination, both within and across instrumental sections. These ideas all ultimately derive from classical woodwind and brass orchestration, which likewise ultimately derive from the idea of interlocking choirs of Soprano/Alto/Tenor/Bass.

*My favourite Drop 2 solo is by Bill Evans on the title track of a later 1975 Milestone release called Green Dolphin Street. It’s the album mostly made up of extra tracks recorded by Evans, PC and Philly Joe after a Chet Baker session in 1958.

If you’re hungry for more on this approach, see Drop 2 More.

There’s more on Drop 2 in my book A Compendium of Jazz Voicings.

Great article , well explained . Thank you

You’re welcome. I only dip by these days – it’s all YouTube now so my written stuff is a niche taste…